10th April 2017 | By Simon Duffy

It is time to assert our equality, the value of our diversity and the need for citizenship.

Many of us believe in justice, and we try and work for justice. But sometimes the “long arc of history” seems a very distant hope. For those of us who work to advance disability rights we see the tide of negative forces rising: cuts, hate crime, eugenics, prejudice and political leaders who have no shame in taking us backwards.

And it is not just disabled people who face intolerance and whose gifts are rejected. The immigrant, the asylum seeker or the refugees faces fear and hatred. People in poverty are increasingly treated as somehow less than human and are subject to political scapegoating. People of different faiths and different sexualities face suspicion and disrespect. Women and children faces ongoing disadvantage and economic systems that seem incapable of recognising true value.

We can see what’s wrong, but we’re not sure what’s right.

We live in confusing times and many of our assumptions about what true justice looks many need to be re-examined. Many of us feel tired and disappointed. The leadership offered by mainstream politicians seems inadequate to the challenges before us. We want a better way, a way more suited to the reality of things.

If we just take the United Kingdom as a case study the growing tide of injustice is obvious to many of us:

The UK is certainly an extreme case. It is the most unequal country in Europe and is cursed with leaders who seem only to want to make things worse. But friends in other countries share some of our problems:

Clearly there are important differences of details; however there is a strong case for seeing these problems as all stemming from the same kind of dangerous and bankrupt mindset.

Firstly many of these injustices are connected by a rhetoric of exclusion and scapegoating. Their message is that our problems are caused by them: the poor, the disabled and the foreigners. We need to keep them out, put them away or keep them down. And this message also contains an implicit threats: Don’t dare to stand alongside them. Stay inside the blessed circle. Trust us to look after you, or else…

When the powerful exploit prejudice in this way the result is never pretty. Rarely does it lead to unity amongst the oppressed. Too often it leads to infighting, fear and further scapegoating. In communities where there is severe economic decline and a lack of power then racism can raise its ugly head. When disabled people are attacked then some may choose to keep their distance from those who are seen as ‘too disabled’.

Malcolm X nailed it when he said:

If you aren’t careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed and loving the people who are doing the oppressing.

Malcolm X

So perhaps we can start with one obvious moral truth: everybody matters. Black lives matter, disabled people matter, foreigners matter, you and me matter. We all matter; we are all equally important.

It’s been said before, but it’s worth repeating: We are all equal.

The UK gives further wicked twist to this rhetoric of exclusion. Politicians now proudly say that we should live in a meritocracy, a world where the ‘best’ rule the rest.

It is hard to know whether to laugh or cry when politicians use this term, for it’s a term of satire invented by Michael Young (who also invented the Open University and many other good ideas). As long ago as 1958 Young argued that, if we’re not careful then society will divide into two classes, and that those in power will increasingly come to think that they are cleverer, and therefore better, than the rest of us and that have the right to rule over us. Today our ‘clever’ politicians make use of the term, but they don’t seem to have the read the book or understood the argument.

Our well-educated elite don’t seem to have noticed that term meritocracy means, going back to its Latin and Greek roots: ‘rule by the best’. But there was already an older term, which in its original Greek form, means exactly the same thing: aristocracy. I wonder what the public would think if they heard our Prime Minister declare that we need to live in an Aristocracy.

Meritocracy is opposed to democracy: rule by the best, not rule by the people. The modern elites really seem to believe that some people are better than other people and these ‘better people’ should be ‘awarded’ with more power, money and status. This is a great philosophy if you already have more power, money or status. It tells you that you deserve what you already have and that those who lack what you have, don’t deserve to get it. You kid yourself that you’re not only richer, but you are better too.

Of course the idea of meritocracy exploits and misuses one important truth: We may all be equal, but we are certainly all different.

Humans are wonderfully diverse. We are blessed with a great range different gifts and needs, which together make us utterly interdependent. We need each other. Human life, at its best enables people to use, share and develop these diverse gifts through different forms of community life.

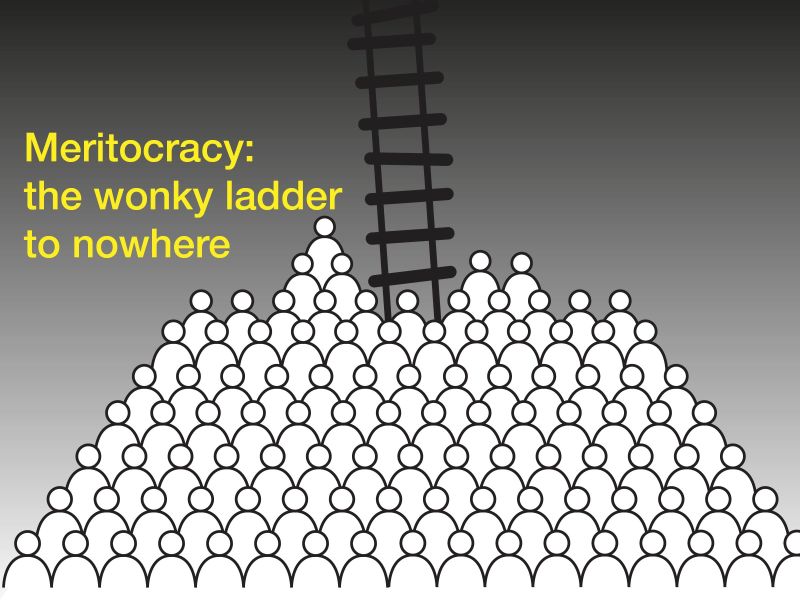

Instead of enjoying the beautiful reality of our humanity the meritocrat imposes their own stupid ladder of values: the clever (as they define themselves) should be on top.

But meritocracy is a wonky ladder to nowhere. Instead of building lives of true meaning, citizenship and love, we are invited to clamber up on top of each other, to rise up to the ‘top’. Quite what we’re expected to do once we reach the ‘top’ is not exactly clear. Perhaps they really do think money, power of fame is the point of life.

Against this nonsense we must assert: We are all equal, We are all different and our many differences are good.

Of course, we have been here before, although it is astonishing that we seem to have forgotten all the lessons of twentieth-century history. Racism, eugenics, extreme inequality and colonialism all fed into its wars, revolutions, the racist and communist terror and the Holocaust.

Out of the ashes of the evils of the twentieth century arose two great social achievements. First, we asserted the fundamental importance of human rights in the UN Declaration and in subsequent conventions. Second, we built systems of social security, education and healthcare to protect people from poverty, insecurity and exploitation. It is telling that today both human rights and the welfare state are under threat.

Today the powerful claim that human rights are dangerous. They want the right to abandon the rules set down in international law. They also claim that we can no longer afford the welfare state. In particular immigrants and disabled people are just too ’costly’. This is all nonsense. Despite all its problems, the world has never been so wealthy. The problem is that we are wealthy, but insecure. As economic anxiety increases then we start to believe those who lie to us and tell us that some ‘outsider’ is threatening our security. How easily we accept the lie that it is the asylum seeker, not the tax evader, who threatens the welfare state.

It is disturbing to see how weak the welfare state has started to become. It grew quickly, offering jobs and services to so many. Then its growth slowed and managers emerged to ration, re-organise and achieve efficiencies. Now, as cuts strike even deeper, many employees of the welfare state (and it doesn’t matter whether they’re employed by the state or by civil society organisations) find that they cannot resist, cannot challenge, cannot become ‘political’ or they will find their own jobs under threat. The welfare state has become a passive victim, going almost willingly to its grave.

What is the cause of this collapse in moral values and commitment to social justice? What can we do about it?

It is easy to invoke big concepts: capitalism, neoliberalism, debt, exploitation. All of these ideas do tell us something true. But if we are not careful we end up feeding our fears. We create an image of monstrous evil that is too big, and too mysterious. We start to feel that there is something inhuman and inevitable about the forces ranged against us. It is important here to remember another lesson from the twentieth-century: never trust anyone who talks about the inevitable march of history, the thousand year reich or the internal contradictions of capitalism. Ideology just means taking one idea to its crazy extreme.

At one level the motives that feed these injustices are all too understandable, all too human the: excessive desire for wealth, power or fame. At another level we know that all these human forms of greed become enmeshed in political, economic and social structures that seem like they’re no longer controlled by human action: bureaucracy, political manipulation, financial markets or corporate exploitation.

But we cannot allow ourselves to given into despair.

Moral collapse demands moral action, and this action needs to start by focusing on problems that we can solve. The good news is that there is much that we can do. There are many ways to make the world a fairer, more decent and welcoming place and there are solutions to our problems around which others can rally. There is no reason to wallow in doom. We need to pick ourselves up, shake off the dust of disappointment and look around and honestly evaluate the reality of our situation.

For those of us who care about people with learning disabilities we have already been taught so much by thinkers and activists who have been sharing their wisdom over the past decades. Wolf Wolfensberger showed us how to protect people from stigma and the threats of being turned into some inhuman ‘other’. Beth Mount and John O’Brien helped us understand how dreams and aspirations can be converted into lives of meaning. Judith Snow and her friends Marsha Forest and Jack Pearpoint helped us see that everyone is gifted and that even our needs are gifts, creating the opportunities for human connectedness. We have a great legacy we must protect and pass on to others.

We have many potential allies. So many other groups of people face exclusion because of illness, disability or being seen as ‘too different’. We need to understand what these groups can teach us so we can help a world that is welcoming of difference for everyone. Many people around the world are learning the power of community action and cooperation. Varun Vidyarthi’s work in India shows us that starting with small groups of people, even with the most minimal financial resources, is no barrier to positive social change. John McKnight’s work on asset-based community development helps us restore a sense of balance and possibility to our local neighbourhoods. Today communities around the world are declaring their willingness to welcome the stranger, the immigrant, refugee or asylum seeker. In my home city, organisations like Assist Sheffield support and protect asylum seekers from the dangerous policies of the UK Government.

This is not an infallible recipe book for social justice, but we know enough already to be hopeful and confident that justice can advance. We can also develop ideas for new social and economic structures that will advance justice for everyone. For example we could campaign for:

The task before us is real and pressing.Even if we are not sure how to change everything then some of the most practical demands of justice are still clear:

There are many great communities out there trying to help make a difference, but we’ve recently launched Citizen Network as a global cooperative to share experiences, projects and to work together to advance the cause of justice and build a world where everybody matters. Why don’t you join us?