20th October 2022 | By Simon Duffy

An exploration of what it means to be middle-class and the dangers of allowing the welfare state to become subject to undemocratic elites.

I don’t really like talking about class. Class makes me nervous. Do classes really exist? I don’t want them to be real. But I think they probably are.

What class am I? What do I feel about that?

Possibly my anxiety is as simple as this. I like to fight on the side of the angels. But I am certainly middle-class by any normal measure. I own my own home; I used to have a well paid job and my parents both went to University. But my Granny and Grandad were not middle-class and I feel that my roots are a mixture of Manchester Irish and Northern Working Class.

Being middle-class certainly seems embarrassing to me.

Anyway. So what?

Well I have been thinking about class and democracy. And it struck me that perhaps there is a way of rethinking the class system, more in accordance with the world we live in.

Class systems are often divided into three parts and in the past they might have been seen like this:

At the end of the 19th century Marx and many others described the battle for justice in terms of class and they were very clear how they thought about the Ruling Class and the Common People. The primary division was between the Capitalist Class and the Working Class. There were other classes and often the term Bourgeoisie was used to describe what might now be called the middle-class. This class conflict was certainly central to how many millions of people conceived the political turmoil of the first half of the 20th century.

But in 1945 it seemed like the class system might be coming to an end. We had universal suffrage (everyone had the vote) and we had the welfare state (everyone could get some help). This was not a revolution but many hoped that this was the beginning of the end of class conflict and all the social injustices which stoked its fires.

And it certainly was a major breakthrough. For the first time the common people could live without the fear of abject poverty, not being able to afford the doctor, not being without a home. This is from my grandad’s memoirs, which he wrote for his grandchildren:

“We had a National Health Service by now, it was introduced by the Labour Government which swept to victory after the war was finished. This was a great innovation. Free medical attention, dental and ophthalmic treatment and free medicine, no more doctor’s bills to worry about.”

However, while these were important benefits, they were not seen as clear political or democratic rights. They made a big difference to the quality of family life, but they didn’t change people’s sense of power or position. And if we look at the welfare state today it seems to me that we can see the class system in full swing:

So far, so depressing. It looks like the class system of old has simply imposed itself on the welfare state and eaten away at its potential to put an end to the class system. Our universal welfare systems make us all equal; but it turns out some of us are still far more equal than others.

Power is concentrated in the hands of politicians and civil servants who might as well live a million miles away from us. Decisions are made to benefit the powerful and the greedy, or to benefit the officer class that runs the welfare state.

Accountability is not to us, the common people, it is to the central state.

The problem is not just that this is unfair, corrupt and patronising. It also means that the welfare state stops functioning effectively. Centralisation of power corrupts our ability to take care of each other effectively - which is what the welfare state is supposed to do.

There are lots of examples, but I am just going to share one from my own experience:

Since 1965 people around the world have demonstrated that if you give disabled people control of the money they need for support then they make better decisions, live happier lives and use these resources more efficiently. Since 1990 I joined that long-standing battle to help shift more power to people and looking back at what we’ve achieved and what the challenges are that we still face then two things are blindingly obvious:

Systems, like Self-Directed Support, at first seem to shift the power towards the common people, but the system itself remains a device under the control of the officer class. So eventually the system puts back in controls becomes increasingly subject to controls which have these kinds of messages:

What should be the person’s own money - their Personal Budget - is turned back into Public Money - and so people continue to be bossed around and controlled.

I have spent a lot of my life in the battle to develop and promote Self-Directed Support. But when I think about how hard it is to make progress and the way in which the system seems to inevitably take back control I have to accept that no merely technical solution is likely. The forces at work seem more fundamental and one reasonable explanation is that the Class System is in operation. The Ruling Class and the Officer Class need to retain control in order to justify their respective areas of power, privilege and income.

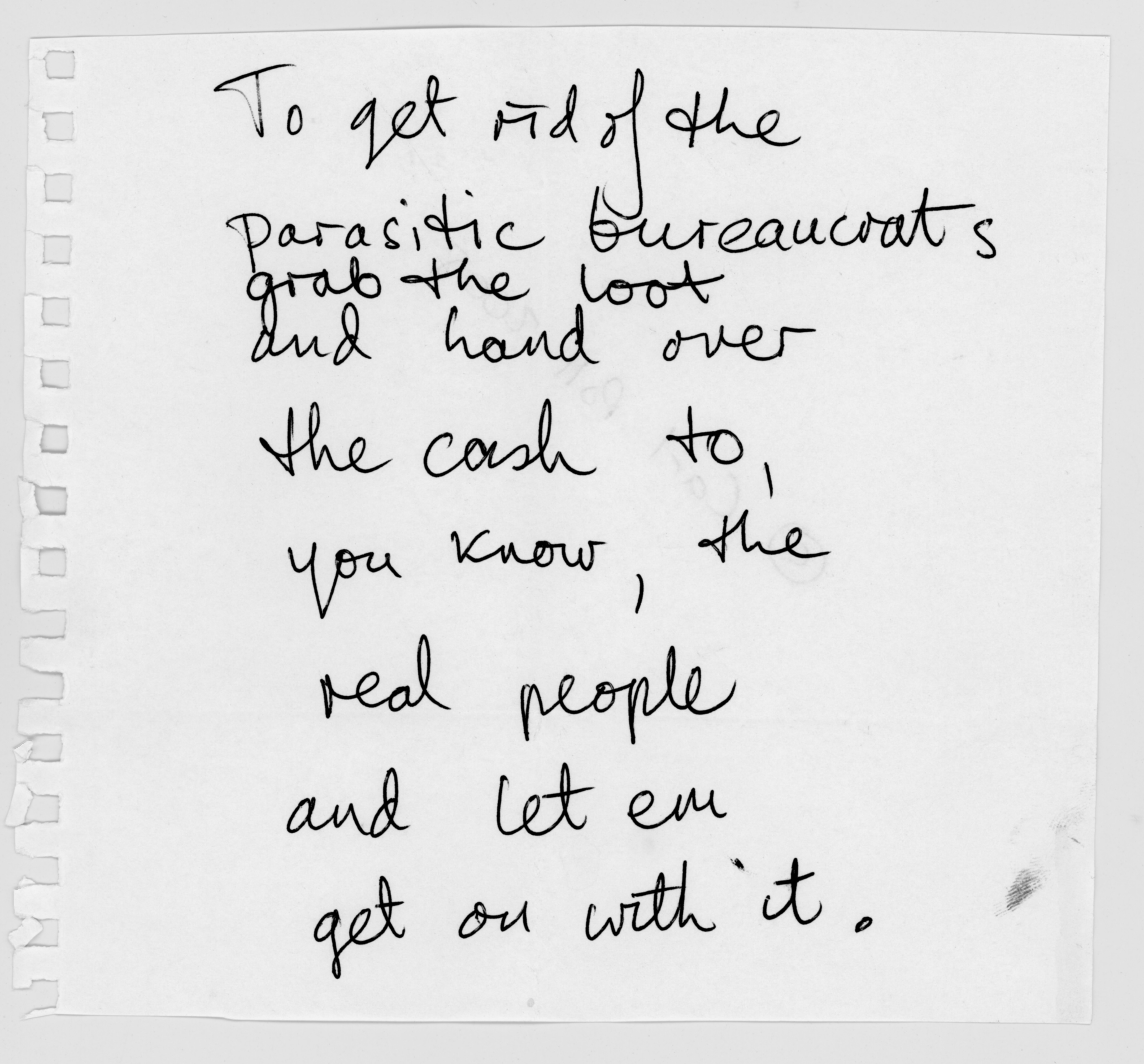

One of my hero’s Carl Poll proposed this as the In Control mission statement. Sadly we lacked the courage to adopt it.

More generally we can also sense an emerging crisis within the middle class - or whoever we are. In the post-war years new opportunities opened up as economic growth, universal education and the growing opportunities created by the welfare state itself enabled many more people to “become middle-class”:

This was not just a straightforward economic change; it was a shift in culture and lifestyle: Wine bars were swapped for pubs; Paris was swapped for Blackpool; Marks & Spencers was swapped for going down the market.

In the UK and in the USA politicians still talk as if the goal is to move all of us into the middle class, following the trail set by our parents or grandparents. Go West young man! Over the hill you will find the land of milk and honey, or at least the land of milk and honey-roasted muesli.

But this is all falling apart. The economic boom has ended and logically there is a limit to how many people can squeeze into these management classes. I read a recent economic report about Sheffield which declared confidently that our challenge was to get more managers into the city. But who are they managing? None of this makes sense mathematically: more managers need more workers to manage!

And we can see the collapse of the middle class everywhere. An analysis of incomes since 1945 shows that from the 1970s onwards the incomes of the poorest 85% have all dropped relative to the richest 15%. Economic slowdown and economic inequality both squeeze the middle-class and close down the chances for people to move from the working class to the middle-class.

Since the 1980s this economic shift is mirrored by political changes that have seen the older post-war generation try to protect their own interests by burdening the young and making it even more difficult to enjoy the privileges of a middle-class life:

It seems that as people move into the middle class they like to pull up the ladder behind them. What is sometimes called social mobility (a very dubious term) has been killed off by those who once benefited from it. This is kind of sad, but pretty normal. Who really thought the revolution would mean everyone was driving BMWs?

Is this all inevitable?

Perhaps more democracy could help us.

Perhaps the problem with the welfare state is that it is undemocratic. Or to put this another way, perhaps our problem is that our idea of democracy is far too weak.

Currently democracy means voting for an MP who leaves your community and moves into a system where they have very little power anyway. In the current centralised system, as the Mayor of Manchester, Andy Burnham told us at our recent Basic Income North conference, all the decisions are made by 100 people in Whitehall who test every possible decision by the question:

“What would the Daily Mail think?”

So obviously we’re all screwed.

Many people want something better which would mean your MP would head somewhere less remote than London. Perhaps a Sheffielder might go to York and ask themselves what the Yorkshire Post thinks. This would be much better. But surely we could we do even better than that.

What about a world where Sheffield people made decisions about Sheffield and people living in the 147 neighbourhoods of Sheffield made decisions about their own neighbourhoods?

This is not crazy. This is how things worked in Athens 2,500 years ago and its how things work in Iceland today.

It is not only not crazy, it will probably lead to different decisions and better decisions. Here’s just three reasons why:

I think this is the only way of collapsing the class system. We, the common people, must learn to be citizens. In the process we will learn that we don’t need a Ruling Class and and all the officers can work for us instead.

To return to my initial personal worry, perhaps my shame has two sources. First of all I loved my grandparents. I don’t like the idea that progress means distancing yourself from those you love, moving away from your neighbourhood or dressing yourself in the clothes of a new class. That all seems disloyal and dysfunctional.

Also I think the acceptance of class seems like the acceptance of a system of superiority. But Boris Johnson - and all his class - are not the superiors of me or of my grandparents. And I don’t want to claim any superiority for myself anyway. Class seems like an invitation to pride - a very dangerous sin - and as Solzhenitsyn put it:

“Pride grows in the human heart like lard on a pig.”