30th September 2022 | By Simon Duffy

What is the case for claiming we are all equal? How can we be equal if we are different? What does it mean to be an equal citizen? These are some of the questions I try to answer.

I was recently challenged by the philosopher John Vorhaus to justify my view that we are all equal. Although his challenge was expressed in the most courteous and friendly way, it was a challenge that cuts to the heart of most of my philosophical and practical work.

I don’t think I persuaded him.

Can I persuade you?

To begin with we had better sort out what we are talking about.

I think that when we are talking about people being equal then I can imagine at least three very different ways of being equal.

Primarily, when we say “We are all equal” what we mean is that we are all equal in moral worth or value. This is equivalent to saying that my unique life is of no more importance than the life of someone who is poor, someone living in another country or someone who has different qualities to me. Men are equal to women, the rich are equal to the poor, the fast are equal to the slow, so on and so forth.

There are probably an infinite ways one person can differ from another person, but not one of those things makes one person’s life more or less sacred, important or worthy of respect. If you are religious (as I am) you might see this as being equal in the eyes of God. But I don’t think you need to have faith in God to recognise the essential moral message of “We are all equal.”

Now I am not pretending this view is totally uncontroversial. We can certainly find philosophers and politicians who are bold in stating that this is not true: Nietzsche, Hitler and Peter Singer come to mind. I guess we might all be tempted down the road of grading human beings or of playing God and trying to determine who should live, who should get the best deal and who should die.

However I do think there’s nothing incoherent about sticking to this basic moral proposition: We are all equal. In fact I suspect that while it might be easy to ask, “Really, are we all equal?” it is a lot harder to say why we are not equal. Once you start trying to pick out one or more features of our diverse humanity as the key to our value then you quickly end up with two gigantic problems.

First, you have the problem of justifying whatever it is you think makes some people better than other people. This is much more difficult than you might imagine. Take for instance a quality like ‘being clever'. Being clever certainly has the appearance of being a ‘good thing’ (ceteris paribus) and we might generally prefer ‘to be clever’ rather than not. But why does this property get to define what makes our life valuable? Why not beauty? Why not goodness? Why not being loved or being loving? Who thinks they can really define the master quality of moral worth?

Worse still, as soon as we start down this road we find that we have undone one of the most basic principles of human rights and common morality. Once one group decides that they have the right to determine that some features of our diverse characteristics is the master characteristic, the key to moral worth, then morality leaves the room. We are no longer safe from being deemed worthless - or at least less worthy: “Some people are more equal than others.”

Of course I can’t tell you why we are all equal. That’s the point. We are equal, because we are equal. It is a fundamental moral truth that needs no further justification. Any justification that seeks to pick out some human beings or (what is basically the same) some property that some human beings have more than other human beings, then you have already abandoned a commitment to equality. You may claim that the property you value is special in some way, but it will turn out that your intuition that cleverness, race, beauty, gender or whatever else they posit, is not only also unjustifiable, it is also dangerous.

And don’t imagine that if you possess the required category yourself that you are safe. The eugenic knife can always cut deeper. You may not be clever enough, beautiful enough or pure enough. Standards can always be ‘raised’.

Perhaps one further defence of my position is that I would rather live in a world where people believed everyone is equal than in a world than where some people thought they were more important than other people. So we can choose, as Athenian democrats did, 2,500 years ago to treat equality as a fundamental principle of our society. It is a moral choice. Other may argue that we should pick their preferred characteristic; but notice that any selection will always advantage some groups and disadvantage others.

2. Equal by description

But we may say, “We are all equal” with a different meaning. For instance we might observe that all people share the same basic needs or we may try and identify some particular characteristics that all people share and which makes us equal.

However, to be clear, this descriptive use of equal has precisely the opposite sense to the moral sense use that I described above. This is often the case in language. We may see a sentence that uses exactly the same words, in exactly the same order, but this sentence can still actually mean an entirely different, or even a contradictory thing.

[Meaning is provided by something that is not found in the words alone; sometimes what is most important is not obvious to the eye. There is a lesson here which is important to my argument.]

If we think about people in terms of their multiple possible characteristics then it seems to me that what is most obvious is that we not equal, we are all different, we are all unique. In fact our marvellous diversity even seems to be part of the wonder and value of our humanity. It is also reflects what Hannah Arendt called natality: the fact that each person born brings new possibilities and new opportunities into the world. Time itself produces difference. The new is always round the corner.

Strangely philosophers and politicians rarely talk about the wonder and value of diversity. They often seem to be in the business of imposing order, grading us and organising us. But walking through the streets of any city what is most striking is not our similarities, but our differences: our different abilities, gifts, shapes, sizes, colours, genders, sexualities, cultures, faiths, habits, clothes, personalities. On and on. However you chop up the world, you will find countless possible differences.

And surely this is a good thing. Who wants to live in a world of people who are the same?

I am not suggesting that we cannot find some general truths that may apply to all of us. I am very fond of Simone Weil’s description of the universal needs of the body and the needs of the spirit and we certainly share human rights. But I don’t think anything that we find we have in common will explain the moral meaning of “We are all equal.” For instance, I suspect it is true that all people contain water; but the sentence “We are all of equal value because we all contain water” doesn’t seem true and I can’t imagine that any replacement for water in that sentence is ever going to work.

Now, to be fair to the equality-sceptic, there is an essential part of my argument which they will want to challenge. I have said “all people are equal” and my use of the term “people” was quite intentional. But I could have said “all human beings” instead; but that would have drawn attention to fact that I do tend to think people have a special value that flies, snakes or even dogs, do not have. Looking at the world through lens of its different species then I certainly tend to think that the moral value of a human life is in some important sense worth more than the life of a fly. This does not mean I think flies have no value (they are an essential part of the ecosystem) but I don’t think I owe any particular fly the same kind of moral attention and concern that I owe another human being.

Now, if someone were to challenge me to explain why human beings were more morally valuable than other species then I’d say three things. First, I am not sure that, as a species, we are more valuable than other species. One of the horrors of the modern Anthropocene Age is species extinction: the irreversible loss of diverse forms of life in the wake of human destructiveness, thoughtlessness and greed. The loss of a species, seems to me, a terrible thing and we should be acting so as to protect the diversity of species. But for most species I don’t think we should think of each member of the species as having the value of a person. That is, I am not arguing that the human species, as a species, is more valuable than other species. It is individual people who matter, and they matter, not because they are members of a species, but because they are people.

Having said that, there may be non-human species that also include people. First, there may be species, not currently on this planet, who are also people. If we met an alien and we recognised them as person (although a non-human person) then we must surely value the life of the alien person on a par with the life of a human person. Second, there may be species already on this planet, who contain non-human people. For instance, there is surely a case to be made that dolphins and whales are communicating with each other much as human people communicate with each other. Perhaps this can be extended further and we may decide that many animals, on closer examination, are also people.

But at this point the equality sceptic will claim that I am contradicting myself. I am claiming that all people are equal, but I am also restricting the class of beings who qualify as people to humans or to some other beings who must share some ‘human-like’ property with us in order to be valued in the same way as us.

So what makes us people (as opposed to human beings)?

The philosopher Kant proposed that it was our rationality: we are rational beings. And his argument is important because he extended this claim by an argument that can be very crudely summarised as stating that rational beings, because they are rational, must value other rational beings. Rationality generates morality as one part of its inevitable logic. [Interestingly Hannah Arendt observed that Western philosophy has drifted away from Aristotle's observation that we are political animals, to a much more dubious, rational animals. This thought is worth pursuing, for political means to be diverse members of a community of action.]

You will be delighted to know that I am not going to try explore Kant’s argument here. His detailed arguments are important, but contested, and I am not fully persuaded by them. Instead I want to return to the nub of the earlier argument.

I think the claim of someone like Peter Singer, who is an advocate of animal rights, a utilitarian and a eugenicist, is that there are some human beings who we have no reason to treat as being more valuable than animals; in fact we might even treat them as having less value than animals, both because they lack this quality of rationality and also they have (in his view) other negative characteristics which are harmful to the world in some way. So the answer he gives to the title of his book: Should the Handicapped Baby Live is, “No, the handicapped baby should be killed (or at least encouraged to die).”

At this point in the argument it is important to note that Singer, like most eugenicists, gets away with this morally outrageous arguments because of general social prejudices. If the term ‘handicapped baby’ was replaced with any other group of human beings then I suspect that most people would be shocked and he would be thrown out of every academic institution in the world. However, in the case of disability, such prejudice is deemed reasonable. This maybe because he has the support of nearly two hundred years of eugenics, propaganda, institutionalisation and general fear and prejudice. So he can mobilise a common prejudice to make the unjustified claim that these people are less than equal.

In fact the argument for his outrageous claim is weak on several counts. First he assumes that disability somehow makes a life less worthwhile and that it also somehow reduces the quality of other people’s lives. But disabled lives are just as interesting and valuable as non-disabled lives, and, even if it matters, there is also much evidence that disabled people, including people with the most complex or severe impairments, have a positive impact on other people’s lives.

But the other problem with his argument is the assumption that some disabled people are not really people because they are not really rational beings. But if you know and spend time with people with what might be called severe intellectual disabilities then you become very conscious of how dubious and uncertain such claims are.

First, you will find that many disabled people, who may be described as lacking rationality are simply cut off from the appearance of rationality for the lack of suitable communication systems, imagination or care. It is dangerous to assume that someone lacks understanding; it maybe rather be that we lack the means to communicate with them. In fact we have not only developed communication systems which show that many people have a world of words locked up inside them, but we have also developed approaches that allow us to understand people without words. Communication has many forms and some languages are highly idiomatic and non verbal. But people who know and love a disabled person always know how to communicate with them.

Second, even if we suppose that some people with severe intellectual disabilities might never think with words or express themselves quite like others, there is no one who lacks character, personality and a rich inner life. It is a failure of moral imagination to not see the person behind the disability. We have no means, nor should we seek the means, to identify the qualities that exclude people from personhood. We need instead to discipline ourselves to look deeper and to value the complex reality that each individual brings into the world.

Another way to make my point might be this. I am saying all people are equal, and that does limit the special kind of moral attention that I am describing to people. But given the importance of people it is essential that we do not limit the scope of that category artificially or recklessly. We may even want to extend the category of personhood to some non-human beings. But trying to exclude some humans from personhood on the basis that we think we’ve identified some dubious test for being a person is dangerous and unjustified.

To put this another way, we don’t need to be the same to be equal, but part of what makes us equal is all the wonderfully different ways we can be different.

3. Equal citizens

So - as we say at Citizen Network - we are all equal and we are all different. But are we all citizens?

In my mind this is a rather different question and a lot hinges on what we mean by citizens.

Although there are lots of different theories of citizenship I’d like to simplify things by the use of one distinction.

Some societies get used to the idea that the word citizen describes a kind of reward or badge of membership. To be a citizen is to be deemed worthy of inclusion in this club. Naturally the value of this club is that it excludes some people and includes others - the citizens. Even societies that were highly democratic, like ancient Athens, used citizenship in this exclusionary sense - only some people can be citizens. It was an honour and you had to be born into a family of citizens.

Now there is no doubt that historically the idea of citizenship has often tended to often have this exclusionary quality. But does it need to? Can we imagine a form of citizenship which is inclusive? Is it possible for everyone to be a citizen?

My experience over the last 30 years of my work makes me feel that we don’t just have a right to think of citizenship as something which can include everyone, but that it must include everyone. In fact I would argue that an inclusive conception of citizenship - one that allows everyone to be a citizen - offers us a more valuable conception of citizenship - one that is closer in meaning to the true meaning of citizenship.

For what is a citizen? If citizenship just boils down to some limited identify of membership - one of us - an Athenian - a white man - or whatever badge you prefer - then the essence of citizenship is lost. The value of citizenship does not lie in the badge of membership, but instead it lies the active membership of a community of equals. The dignity of citizenship does not lie in having a passport. (Anyone can have a passport; even Boris Johnson has a passport.)

The dignity of citizenship is linked to its commitment to a political vision which flows from our moral equality. Citizens are equal and different; citizenship is a means for seeing our innate equality without losing sight of our wonderful diversity. Citizens bring together their diverse gifts - including their needs and frailties - and from these gifts they create a community that honours everyone as an equal.

So, in a fair society, we treat everyone as a citizen and then we invite and support everyone into deeper and more active forms of citizenship. This kind of citizenship is what Kant describes as an imperfect concept: I can always be a better citizen. The ideal is real, but the form our citizenship takes depends on the choices we make and the support we receive.

So equal citizenship, is in this sense, an ideal of political or social life. Everybody who is here (and where ‘here’ is can stretch from my street to the globe) is a citizen. Nobody can be excluded. When you live in a Fascist state or modern Britain, when the police or social services arrive to take you away, then they are breaking the bonds of equal citizenship. This is true even if the Law and the Government provide them with their justification.

We all belong, whatever the law says.

So, we are equal and we remain equal, even if someone wants to claim they are superior.

We are different and that’s a joy, even if someone says that we should all be like them.

And we all belong, even when someone wants to brutalise or exclude us.

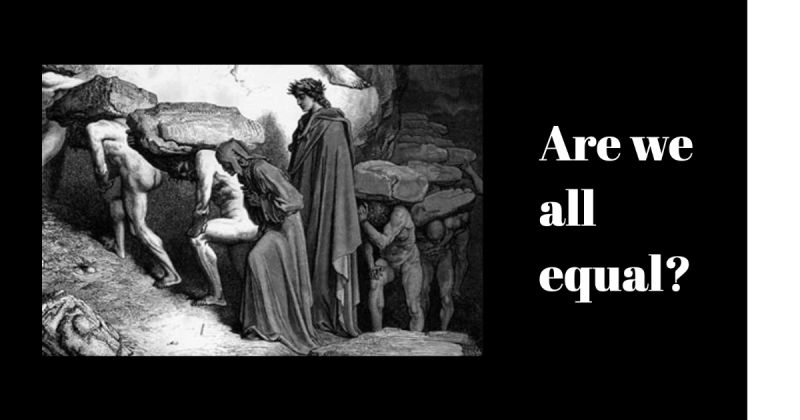

There is a truth in this despite the fact that there will always be those wanting to elevate themselves, make us conform to their standards or who wish to exclude us. The problem is not that we can’t justify our equality. The problem are the endless temptations of pride, envy and anger, which as Dante tells us, are the three most vicious of the seven deadly sins.