7th October 2013 | By Simon Duffy

We should not be afraid of the language of entitlements for entitlements give meaning to the idea of rights.

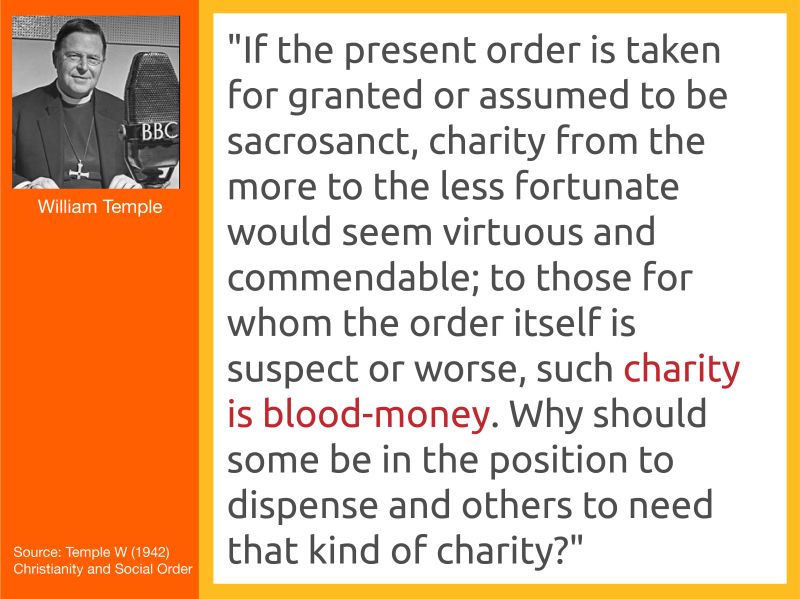

If the present order is taken for granted or assumed to be sacrosanct, charity from the more to the less fortunate would seem virtuous and commendable; to those for whom the order itself is suspect or worse, such charity is blood-money. Why should some be in the position to dispense and others to need that kind of charity?

An infidel could ignore that challenge; for apart from faith in God there is really nothing to be said for the notion of human equality. Men do not seem to be equal in any respect, if we judge by available evidence. But if all are are children of one Father, then all are equal heirs of a status in comparison with which apparent differences of quality and capacity are unimportant; in the deepest and most important of all - their relationship to God - all are equal.

William Temple, Christianity and Social Order

This quote perhaps helps remind us that the Church has often been a powerful advocate of real social justice. Archbishop Temple does not seek to position the Church as a bestower of charity; instead he demands that society recognises the genuine rights that are created by our human needs.

He also reminds us that equality is the foundation of social justice - we simply are equal - in some profound moral sense - despite all our obvious and great differences. This fundamental equality of moral worth is central to our moral codes (whether or not you believe in God). There is also an aspiration that many of us share - to live 'as equals' in a community where those differences can be reconciled through our equal citizenship. The barriers to such social equality are great indeed - but the moral appeal of such equality is hard to erode - despite all the prejudice, discrimination and injustice that is such a feature of the modern world.

An example of this battle for equality is the conflict over 'entitlements' that rages around people with disabilities internationally. In the UK today the entitlement to social care is under a double attack: (a) funding for that entitlement is being cut by 33% (from 2010 to 2015) and (b) many local authorities are now undermining a policy position which had treated 'personal budgets' as the person's money - an entitlement. Instead people find their control eroded by increasing regulations, bureaucracy and direct interference.

On the other side of the world, Australia, as it begins to implement its National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), is making a globally important commitment to secure the rights of persons with disabilities in line with the UN Declaration and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. However, even in this context, policy-makers struggle with the idea that disabled people are actually owed the intended budgets - that these budgets are entitlements which belong to people:

"It's Jack's money, not the government's money."

I will not rehearse here all the arguments for treating such funding as an entitlement (I have done it elsewhere and I have the feeling I will have to have another go soon). I simply want to observe the starkness of the choice:

If we give people money they are either entitled to it or they are not. If they are not entitled to it then why are we giving it? We would be giving what we ought not to give. If they are entitled to it then it is theirs - not ours.

What is at stake here - as Temple rightly observes - is whether we are giving people what they are properly due, or whether we are just giving the blood money of charity.