16th June 2018 | By Simon Duffy

Why are the severity of the cuts to social care so hard to communicate?

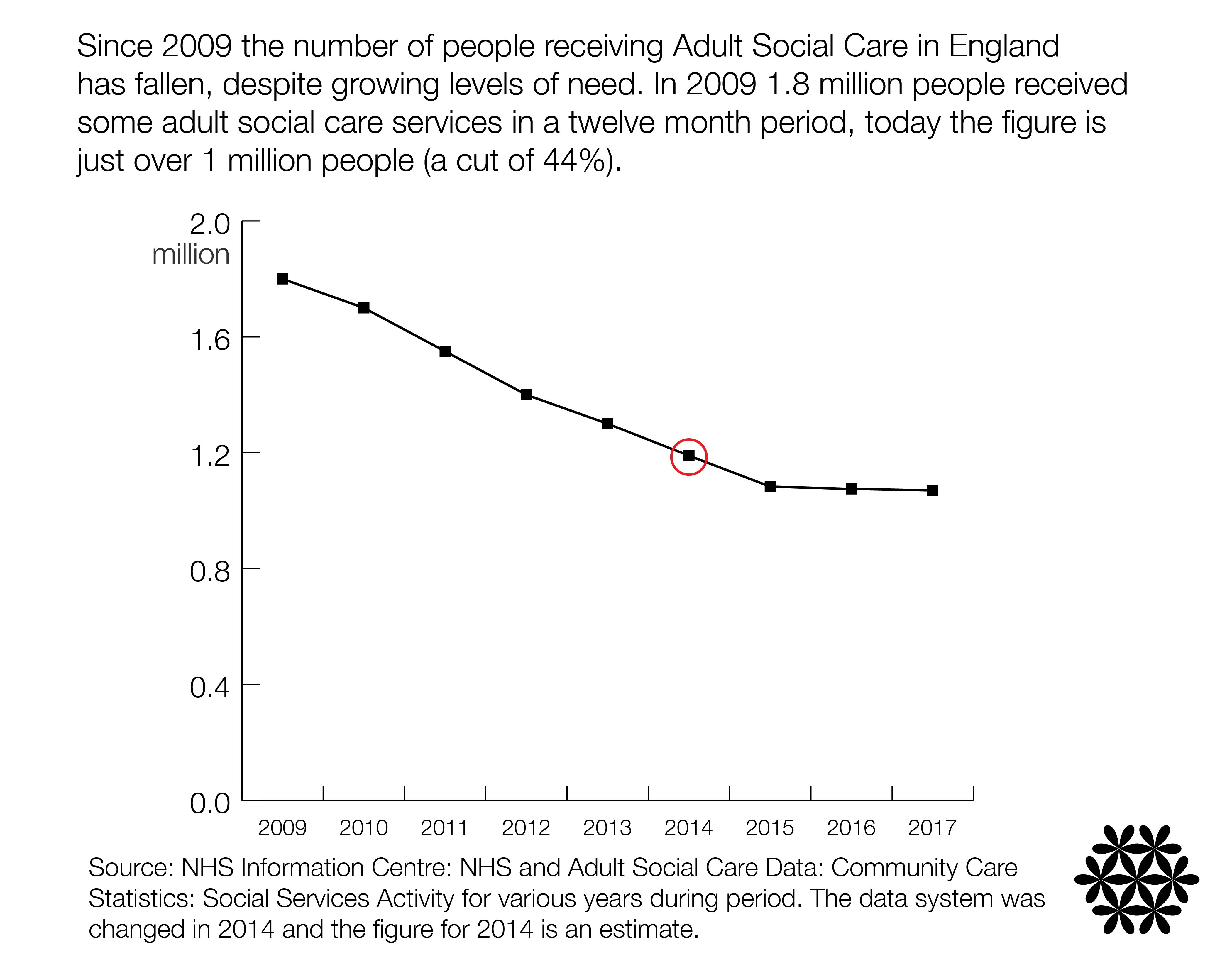

This week I have been working in the USA, but it's been hard to get people to understand how severe the cuts to social care (children and adults) have been in England. But here’s my best shot at a metaphor:

A family is crossing a busy road. The traffic lights is red, the family crosses, but a car ploughs into the whole family - children, parents and grandparents are scattered across the road, bleeding, broken and dying. The car stops and a drunken driver leans out of the car window and shouts, “Don’t worry I’ll go and get help.” But when the car arrives at the hospital it smashes straight into the side of the ambulance. The Government - which keeps promising to help social care - is the primary source of the disastrous cuts to social care - but somehow we keep normalising their destructive behaviour. Cuts to children social care have also been vicious.

Cuts to children social care have also been vicious.

This is because central government has cut funding to local government by about 60% or more, and these cuts are deepening every year. Since 2010, we’ve been told:

As an Englishman there are many deeply upsetting and shameful aspects to what is happening in my country:

None of this necessary or fair. Social care has always been a small, but important, part of government expenditure (about 1-2% of GDP). It is low cost and relatively efficient. It is a preventive service which, when it’s working well, reduces the money spent on healthcare or on forms of institutionalisation.

The UK Government’s policy has also been severely condemned by the United Nations as a breach of human rights, and yet it continues unabated today. Even worse, this policy is just one part of the Hostile Environment created for people and families with disabilities: cuts to income security and housing combined with the growth of mean-spirited systems of assessment, control and sanctions are driving up rates of suicide and depression.

There is still no sense of national scandal and no sense of accountability on the part of our rulers. Grass roots organisations like Disabled People Against the Cuts (DPAC) have tried to force this issue onto the agenda but there is still no effective national campaign that combines the many powerful groups and organisations involved directly or indirectly with social care.

It doesn’t need to be this wayIf the leaders of opposition parties, trade unions, major charities and local government could open their eyes, listen to people and work together then this policy could easily be reversed and a new direction set.

I would ask everyone who works in the social care sector, but especially those who are likely to retire with a good pension one day, to think about this problem and ask yourself:

What do you want to be remembered for when you’ve gone?

You survived the car crash

Or

You helped turn this problem round