18th January 2017 | By Simon Duffy

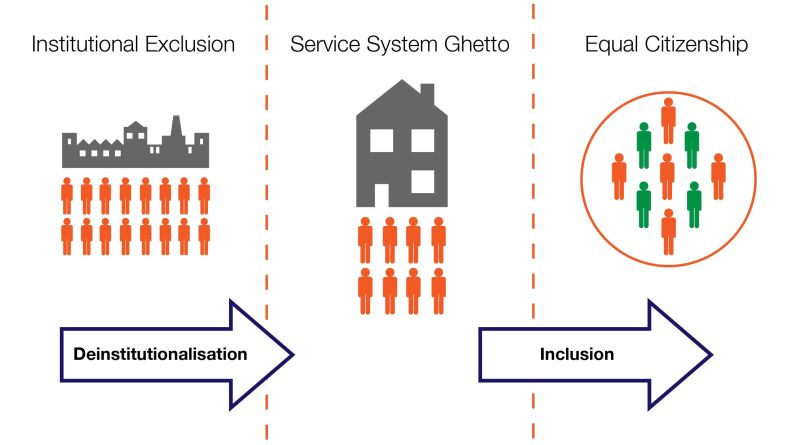

Community care is not acceptable if it means creating care ghettos rather than enabling full citizenship.

I was recently invited to speak to a room of commissioners for services for people with learning disabilities in England about progress on de-institutionalisation. This is a pretty rare event for me these days and so I was keen to make the most of the opportunity.

I called my talk ‘Who Put Out the Fire?’ and I wanted to talk about why there no longer seems to be any significant passion or momentum for inclusion or for further deinstitutionalisation. I do not mean that nobody is doing good work. As ever, there are brilliant people doing wonderful things across our communities. But overall the passion that used to exist to bring about positive change has evaporated. In fact, in some places, we see things going into reverse.We are at a moment of change.

Progress is not inevitable and we should not be naÏve. Things are beginning to roll backwards and, unless we change our behaviour, things will get much worse. Eugenics is already back on the agenda, in the form of genetic screening for Down Syndrome, ongoing practice in neonatal care and abortion laws that abandon limits in the case of disability. These practices go hand-in-hand with the meritocratic beliefs of our elites - people who think that the ‘clever’ (themselves, by their own definition) deserve the ‘best’. Putting powerful technology in the hands of people who think that they are better than other people never ends well.

And the institution is back. Not only are thousands still incarcerated in private hospitals (at great expense) but also authorities are now being tempted by that old dreadful excuse for bad practice: economies of scale.

Some of this can be explained by austerity. Politicians and managers have always been tempted by the idea that ‘congregate care’ must be cheaper and that they have a public duty to manage costs and be ‘reasonable’. This is understandable when local authority funding has already been cut by 30-40% and is being further cut today. Local commissioners are only following the lead of national politicians when they shift the burden of the banking failure onto disabled people and families.

However, more controversially, I think that some of the responsibility for today’s failure of leadership lies with Valuing People. I do not mean that the Valuing People policy or its leaders were bad - quite the opposite - but I do think the whole process has led us up a creek and today everybody seems to have forgotten how to paddle. Genuine, community-based leadership, is missing in action.

In the 1960s and 1970s many leaders emerged, inspired by Wolf Wolfensberger’s ideas, shocked at the state of our institutions or simply keen to ensure their sons and daughters were able to get a better deal. These leaders challenged the norm and created new alternatives. Many of the organisations (like Mencap) which we take for granted today earned their leadership status through this process of challenge and creation. Later on other organisations, like the Campaign for Mental Handicap (which became Values Into Action) took on the role of challenging Government and of advocating for human rights and inclusion.

But Valuing People encouraged people to put their faith in two dangerous myths. First, that Government did care, and would continue to care, about the fate of people with learning difficulties. It didn’t, it doesn’t and it won’t. Second, positive change comes from Government and from the leaders it selects.

By this I don’t mean that Government is bad or hostile to the interests of people with learning difficulties. It isn’t. But Government is always late to the party. The job of a civil servant is to keep everybody happy, not to lead radical change. The job of a politician is to respond to democratic pressure, not to stand up for powerless minorities. Entrusting leadership to politicians and civil servants is to abandon leadership.

It seems to me that Valuing People killed the real drive to inclusion; just as Putting People First killed the drive to self-directed support. Killed with kindness, killed with money, killed by assuming an intellectual authority it could never possibly live up to.

This seems counter-intuitive. Too many good things, too much useful funding and too many opportunities are associated with Valuing People to believe that it was bad for us.

But look at England today.

Where is the self-advocacy movement? In tatters. Today the Government is about to take away the last piece of funding for the National Forum and for the National Valuing Families Forum. If this goes then can we look back on over 30 years of self-advocacy development and congratulate ourselves on our achievements? No. Self-advocacy is patchy, under-funded and lacks any agreed form of leadership.

What about service development and innovation? For some reason we now expect government and commissioners to lead innovation; but our systems of commissioning have effectively killed off innovation and creativity. Some people and families have escaped the system, using direct payments; but most of the money remains invested in the care home system (which is now protected from the impact of personal budgets).

Today the whole sector seems incapable of defending itself or of uniting with others to fight for justice. For example, there is no effective campaign to defend social care. Many of the leading organisations seem too dependent on Government funding and unwilling to speak out or get organised.

If you look upwards for rationality and for inspired leadership you’ll be a long time waiting.

The positive changes that began in the 1970s were led by people and professionals, starting from where they were then. Focused on what they could do with the resources they had to hand. They did not expect everything to be done for them. They got organising, supporting and campaigning. That’s how things really change.

Perhaps one thing that they also had back then was a strong sense that the current system was unacceptable. They looked at the institution - those systems of absolute exclusion - and they declared that it was absolutely wrong - and they then worked hard to build an alternative.

In practice that alternative is the world er have now: group homes, day centres, respite services and care services. This is a significant improvement over the old system. This is the system that is today’s ‘normal’. This is the system we are struggling to improve and which is now beginning to slip backwards into something worse.

Why can’t we do better than this?

What can’t we dream bigger than this?

People with learning difficulties are agents of social change. They can bring communities together, they can break down the barriers of pride and illusion that leave us dislocated and alone. They can offer the rest of us a different sense of the purpose of life and insight into the joy of living.

People with learning difficulties are just different. But we are all different… get over it.

Diversity is a good thing and to be welcomed. True equality is not found in sameness, conformity or compliance. Equality means treating each person as if they belong, as if their gifts have meaning and value. Equality demands we treat each other as citizens - working together to create communities that welcome and nurture our gifts.

If you believe this then this belief has real life consequences.

One of these consequences is that we must start to acknowledge that the community care system, that was developed during the period of deinstitutionalisation, is totally inadequate. It is a system of ghettos, small segregated communities, cut off from community life and communicating to people on both sides of its walls that people with learning difficulties don’t really belong in our communities.

Ghettos are not evil. Community care ghettos are not the same as the long-stay institutions that they replaced. Ghettos can even be fun and interesting. Ghettos can even convert themselves into places of community and inclusion. (It would be a mistake to confuse ghettos with institutions and it would be a mistake to ‘close’ ghettos using the same kind of process that were used to close the institutions.)

The architects of new and inclusive communities will be people themselves. But they will need help from families; and they will need help from the professionals who want to be true partners. And they will need help from fellow citizens who want to live in the kind of community that can welcome each of its members.

Is this progress inevitable?

No. Today it’s being undermined by powerful social, economic and political forces that are being left unchallenged.

Is this progress a pipe dream?

No. It is happening now, in small pockets. There are people and places that are showing us the way forward. Rising to this challenge takes work, it takes time and it takes creativity. But it’s worth it.

What I am trying to do is reframe the challenge that lies before us. We must stop treating the current community care system as if it provides an acceptable norm. It does not. We have to be honest about the limitations of what we’ve achieved. There will be no increased hope, passion and wider social movement unless there is both a compelling vision for inclusion and a growing sense that the ghettos we’ve created are unacceptable.